Can we create new tools and capacity-building strategies that enable Hmong American youth leaders to address social issues in their communities?

This ongoing thesis work uses design-led research and participatory methods to create collective goal-setting tools for Hmong American youth leaders. In collaboration with the Hmong and South East Asian American Club at the University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point, we used insights from this process to co-create community action plans and strategies. This three-part initiative includes: 1) externalizing the Hmong narrative through audio and visual multimedia work; 2) creating open-source collective visioning tools to allow for social dreaming, aspirations, and frictions to come to the surface for productive community conversations; and 3) a digital platform which archives not only the past, but possible futures and action plans across borders in Hmong diaspora communities. We hope this work can contribute to a larger discourse surrounding translocality and belonging in today’s hostile sociopolitical climate.

Understand Environmental Conditions

Establish Design Principles

We compiled a set of research-based principles as the criteria for our design strategy.

Enable vulnerability. Having voice and resisting oppression makes one vulnerable.Can we navigate spaces of discomfort and complexity with dignity and support rather than shame?

Allow for productive friction. Is a shared, collective voice always preferable? How can we create space for alternate voices and tensions to arise, so issues become visible before a crisis happens?

Address multiple scales of intimacy. How does the ethics and morality of memory affect the strategies needed to create shared intimacy at different scales, across both thick (family/community) and thin (other/stranger) relations?

Design for transition. What privilege and power do we have? How do we share, transfer and give up power? How might we redefine leadership so that we may move forward and build momentum?

Accessible, mutable systems. Obtaining resources and responding in a timely manner are an issue for advocacy and mobilization efforts. How might we make these tools and systems accessible, scalable, and open source?

Envision translocal strategies. Recognize the interconnectedness of different localities, drivers and social factors that enable and disable mobilization efforts.

Model a New Code of Ethics

Our ethics aims to address the way that we conduct our research methodology.

Sincerity. Be self-reflexive about our individual values, biases, and inclinations as designers and researchers. We need to be transparent about the methods and challenges we encounter.

Vulnerability. Allow ourselves to be humble, honest and vulnerable. Engage in a way that dismantles traditional power relations and acknowledges community expertise. Ensure that the narratives we reveal are not co-opted or taken out of context.

Co-presence. By walking with others, sharing meals, and living alongside the people we meet, our goal is to explore the “sensory nature of sociality” as we attempt to see the world and live and move as others do.

Action-oriented. Take an action-oriented approach that aims to change social structures and practices. Respond to real-life, contextual issues and beliefs. Create stronger relationships through this work.

Resonance. Conduct multimodal research that is meaningful, evocative, aesthetically affective and transformative, while remaining true to the people we are representing. Extrapolate our findings in a way that is understandable and transferable.

Sensitivity. When working in spaces related to displacement, refugeeism, memory and trauma, we must be careful not to re-traumatize others through our work. Design is not neutral, and even the best intentions can have harmful consequences. Navigate these areas with sensitivity, respect, and care.

Design the Research Methodology

We took a multimodal research approach to reveal a more nuanced, multifaceted snapshot of our context. To do so, we used the following methods:

Propose New Tools for Advocacy Efforts

The ladder of engagement is an organizational framework that aims to deepen user engagement. In adopting its model as a basis for our design strategy, we seek to bring those who are unaware of issues to become observers; those who are observers to becoming supporters; and those who are supporters to becoming advocates for their communities. We focused on designing for these transitional spaces, using a three-part approach:

Film/Soundscapes to make issues visible through voices in the community

Open Source Tools that can be employed and adapted independently, without expert facilitation

Online Platform connecting generations to strengthen social ties

Work Towards an Action Agenda

Through meetings and conversations with HaSEAAC members, together we began to map out key players in Wisconsin’s Hmong community. This practice was very useful in helping us understand the power dynamics in this network and who holds authority. For example, the Hmong 18 Council, Inc. is a coalition of elders in the Hmong community that provide leadership across Hmong diaspora communities in the United States. To involve more of the newer generation in their decision making, they recently asked HaSEAAC for input on community issues. However, HaSEAAC was skeptical about this opportunity, since in the past the Hmong 18 Council had never seriously taken their views into consideration. As a result, this led to a discussion over whether asking for input was a form of tokenism that worked to maintain existing power structures in the Hmong community.

Through this practice, our goal was to begin understanding where power lies in this ecosystem. In doing so, we can collectively start to target and redistribute power to better enable effective advocacy efforts by youth organizations in the community.

Create Community Visioning Tools

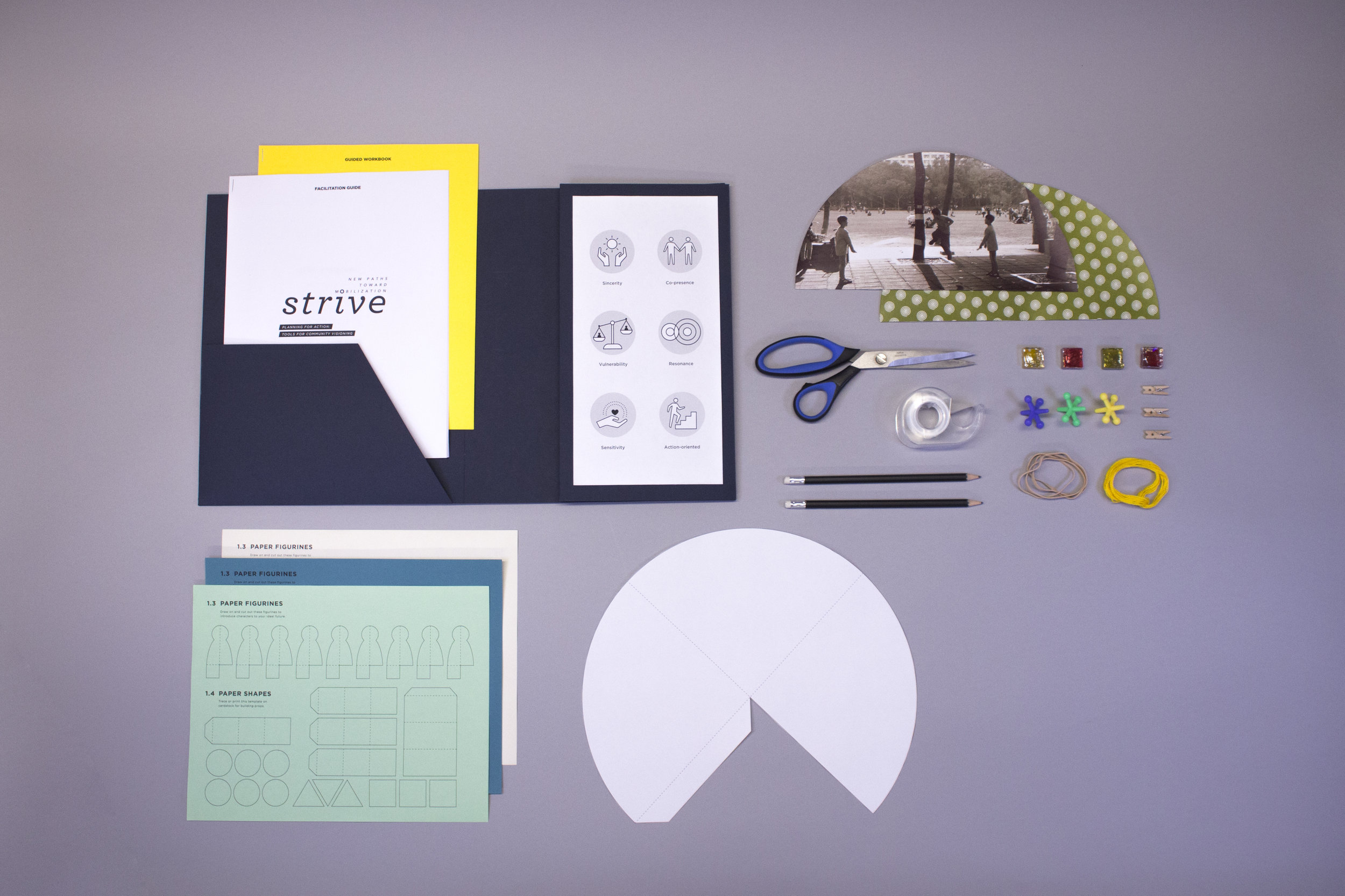

Based on the results of our research and insights gained from validating our research findings, we iterated on the materials of our futuring workshop. Our goal is to make these materials widely accessible, easy to use without expert facilitation, and adaptable to the needs of the individuals or groups using them. The final pdf files that we have made available online include the following components:

Facilitation guide for non-experts

Guided workbook for participants

Printable templates for the diorama, backdrops, and props

Customizable materials checklist

Example photos of prepared and customized tools

Design New Strategies for Connection

In launching the most current version of these tools, we plan to reach out to our existing list of community and student-run organizations who may be interested in collective visioning and action-oriented infrastructuring practices.

We have already received positive messages from the Center for Hmong Arts and Talent in Minnesota, who were interested in a previous iteration of our collective visioning tools for use with youth leaders attending their programs.

Our current area of study for this work focuses on a particular diaspora community located in the United States and designing tools that bridge gaps in their pathways to effective mobilization. Eventually however, our goal is to enter spaces of overlap and intersectionality with the transferability of our findings and tools. We envision a future where analogous groups can adapt and build on these tools to meet their needs. In creating a way to share back the action plans that each team develops, we can begin to identify new forms of solidarity and connection across communities and geographies. In the long run, we see this as an example of actually putting translocal strategies into practice.

Propose a New Code of Conduct

Several tensions arise when doing research that traverses disciplinary boundaries.

As transdisciplinary design practitioners, one of these issues is the potential abandonment of established guidelines, ethics, and protocol. Ethnography, sociology, anthropology and other established disciplines of study are regulated by a code of ethics that oversee these interactions, engagements and operationalization methods, especially in a participatory context. While in a design context these regulations can be seen as a restriction and hindrance to trying out new ideas in unpredictable spaces (prototyping), it can become extremely problematic when working with members of “vulnerable” populations. In response, we propose a new set of ethics that embody our stance on the future of design practice.

As practitioners, we aim to apply our design process to real-life scenarios with honesty and integrity. By focusing on a specific case-study about the Hmong community in Central Wisconsin, we can demonstrate how the individual components of this new Code of Conduct can manifest on a distinct and human level. Our goal is to reveal the ways in which we can apply this new Code of Conduct in practice. Each code works to contextualize certain steps of our design-led research, demonstrating the importance of each point in building a more ethical and just practice.

Impact and Next Steps

Using the insights from this case study, we are exploring transferable resilience strategies for other marginalized populations who are facing similar challenges. With this initiative, it is with hope that we can begin to understand how we can begin to aid and provide analogous communities with tools to empower and give voice, so their stories can be heard. As we continue our work, we plan on disseminating our findings across both design and academic communities, in hopes of modeling a more socially just and ethical way of conducting design-led research.

Featured

HaSEAAC 2017 Spring Conference (Stevens Point, WI)

VergeNYC 2017 Conference (New York, NY)

Bedford+Bowery (online)

TRANSDISCIPLINARY Design Thesis 2017

Parsons School of Design (online)

Roles

Strategy, Design-led Research, Workshops, Art Direction, Videography

Team

Ker Thao, Winnie Chang, University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point

Dates

January–May 2017